by Jay Baker

It’s pleasing to look back on the last entry to this column and see that our aims and hopes for this season are being realised – after a challenging start, we’ve found our rhythm as a cohesive unit, despite a series of injuries hitting the squad, and we’re well on our way to realising our “2020 Vision” (and we came up with that last May, by the way, long before social media accounts started using the term this year for everything from political campaigns to marketing methods!)

It’s pleasing to look back on the last entry to this column and see that our aims and hopes for this season are being realised – after a challenging start, we’ve found our rhythm as a cohesive unit, despite a series of injuries hitting the squad, and we’re well on our way to realising our “2020 Vision” (and we came up with that last May, by the way, long before social media accounts started using the term this year for everything from political campaigns to marketing methods!)

Beyond the hopes expressed here last time, there have also been some pleasant realisations of events I was less certain of: opposing coaches, some from top teams, taking a loss to us and still crediting us for our advanced playing style and deserved victories. That’s been refreshing, and a long time coming.

But not all coaches are like that, of course. I’m sad to say that this league is rife with coaches and other figures from football clubs perpetuating ignorance and prejudice with a level of toxic masculinity that is bitterly disappointing. This is a women’s league, and yet the sexist views of some still continue – demonstrating the reinforcement of patriarchal perspectives that have long been trickling down from the very top of the Football Association, an organisation that – despite the years of scandalous statements and actions from high-ranking management from Glenn Hoddle to Mark Sampson and Phil Neville – now claim they “only do positive,” when my actual counter-cultural, genuinely positive approach at AFC Unity’s beginnings provoked numerous visits or complaints from local FA officials and members of the league committee at the time (and an intentionally stress-inducing nine-month long – ultimately futile – case against me) because I dared to call out racism and bullying and cliques back in the day – apparently, though perhaps unsurprisingly, a shock to the system for the footballing culture. It seems, even at this low level of grassroots football, I had to be challenged for daring to question the way things had always been.

So on reflection it should in fact be no surprise to me that I’ve seen ignorant views continue to be expressed by my peers. Likewise, it should be no surprise to them that I’ll be part of the challenge to it, as Head Coach here at AFC Unity.

In recent years we’ve been given numerous awards for our ethos and initiatives, from Football for Food to Solidarity Soccer, the latter of which demonstrates that there is a place, a safe space, for those let down, rejected, or failed by the traditional football system and its culture.

Some of the blame has to go back to the top: women’s football all too often emulates the toxic masculinity of more prominent men’s football on newscasts and sports channels and newspapers and social media everywhere. An inherently capitalist endeavour like the Premiership, for example, is a huge part of our culture. The ban on women’s soccer from football league grounds was only lifted five years before I was born – I was pulled from school by my mother at age 11 due to bullying, in part because my best friends were girls and I even preferred to play football with them, provoking a violent response from the boys in the playground. But even after the ban was lifted, and growing up in the hometown of the Doncaster Belles, there were stereotypes about women who played, whether they be “tomboys” or “butch,” and meanwhile Justin Fashanu, the first black footballer to warrant a £1,000,000 transfer fee, came out as gay and was driven to suicide by the victimisation against him as part of a culture that continues to this day, where openly gay men in football are few and far between.

While we can’t undo the damage of the past, we can learn from it and realise that outdated prejudice and stereotypes have to go. “Sex and race,” feminist activist Gloria Steinem once stated, “are easy and visible differences, (and so) have been the primary ways of organising human beings into superior and inferior groups and into the cheap labour on which this system still depends.” This is key: binary differences have been used and abused to categorise people and thus create hierarchical systems crucial to capitalism.

But Steinem’s own views have evolved, into the modern realisation that – as with the kids taught alongside me in my school years – gender is essentially a performance: the boys in my school were taught to play football, be aggressive, and pursue outdoor activities, for example, while the girls were taught to wear skirts, play with dolls, and learn to bake, and even one little kid like me challenging that was a shock to the system, to the point where the kids themselves actively reinforce those norms – “girls don’t play football,” they’d angrily shout, and “boys don’t play with dolls,” and so on.

“There’s a story,” said gender theorist Judith Butler, “that came out (a few) years ago, of a young man who lived in Maine, and he walked down the street of his small town where he had lived his entire life – and he walked with what we call a ‘swish,’ his hips moved back and forth in a ‘feminine’ way, and as he grew older that ‘swish’ became more pronounced and it was more dramatically ‘feminine,’ and he started to be harassed by the boys in the town, and soon, two or three boys stopped his walk and they fought with him, and they ended up throwing him over a bridge, and they killed him.” She continued: “So then we have to ask: Why would someone be killed for the way they walk? Why would that walk be so upsetting to those other boys that they would feel that they must negate this person, that they must expunge the trace of this person – that they must stop that walk no matter what; that they must eradicate the possibility of that person ever walking again?” It’s a deep panic or fear relating to gender norms, she explained – that people experiencing this will go so far as to require boys to be “masculine” or else possibly even be killed.

These are some of the reasons why, as many of our players will tell you, programmes such as Solidarity Soccer are important – it not only nurtures players in our positive playing style and more holistic approach, but it rejects toxic masculinity and those gender norms. It’s why the players are leading the way in ensuring that it becomes even more inclusive as part of our revolutionary 2020 Vision – a safe space for women, trans, and non-binary people. Cisgender men have had their time dominating football (and indeed still do), alongside pretty much everything else, so again it’s time to provide a counter to that culture, and at AFC Unity we plan on doing just that.

This year, as part of the 2020 Vision, we want to be more inclusive for the LGBT+ community, open up forums for feedback and input, and help create safe spaces and educational resources. Nobody’s perfect – I’m far from it – and we can all educate ourselves and learn more; Amnesty International is by no means a radical organisation and yet even they provide a decent starting point of education on this issue, which you can read here.

When I was a regular guest on BBC Radio Sheffield, as the Head Coach at AFC Unity I used to get asked the same questions over and over again about women’s football: about the supposed positives of professional football for women, its money-making developments and related raising profile (all of which I personally reject, as I’ve stated here before), and whether women will play against and alongside men. It’s an interesting prospect. With the ban now distant in our rear-view mirror, the cause of women’s football is of course a very important one. But if its feminism isn’t intersectional – if it doesn’t also stand up for trans and non-binary people as well, who have long been victimised – then it’s buying into the same harmful hierarchical attitudes that oppressed women in the first place.

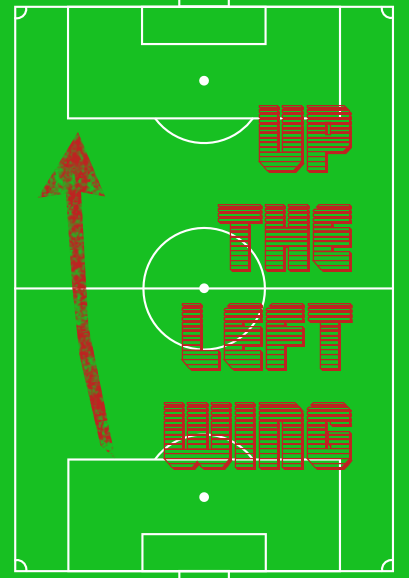

The views expressed in “Up the Left Wing” are those of Jay Baker and do not necessarily reflect those of AFC Unity or any of its personnel or players