by Jay Baker

by Jay Baker

I only ask this of you. I won’t tell you off if you misplace a pass, or miss a header that costs us a goal, as long as I know you are giving 100%. I could forgive you any mistake, but I won’t forgive you if you don’t give your heart and soul to Barcelona. The style comes dictated by the history of this club and we will be faithful to it. When we have the ball, we can’t lose it. When that happens, run and get it back. That is it, basically.

– Pep Guardiola, in his first speech as Barcelona manager.

Many people fear, and therefore resist, change.

Football is changing. Some players don’t like it. Many fans don’t like it. The English press certainly don’t like it – partially fueled by xenophobia of “foreign” managers coming into English leagues and introducing different styles; different philosophies.

We have former footballers of questionable ethics complaining that players have to endure the same coaching programmes as managers, as though they have an understanding, or a head start, that managers don’t. In fact, many of the best managers are those who played very little football, especially at a top level (just look at Arsene Wenger).

I’ll go one step further: the tutor who got me my first coaching badge told me that all the experience and even badges in the world don’t matter if you don’t have heart, passion, or leadership qualities as a person. Not, in fact, English himself, he also acknowledged a deep-rooted problem within the English game and its resistance to evolving from its own traditional ways (not least the army camp culture of an otherwise-clueless Level 2 coach abusing their power to scream and shout at players, free from proper regulation). This is what’s held back English football, but few admit it.

Hence, the English press complain when a “foreigner” like Pep Guardiola comes in and influences an adjustment in the way football is played in England, too. Many managers bring in players from overseas to play this way, admittedly building a glass ceiling for English talent and limiting the potential of the English national men’s team. It’ll happen with the women’s game as well, as money begins to carry it away from its grassroots spirit and into corporate boardrooms.

But change, good or bad, is inevitable. And the way football is played is changing – which is a good thing.

In an 1872 international men’s game, Scotland surprisingly contained England because they chose to pass the ball around – play possession, unheard of at the time – rather than simply run on goal. While much junior football hasn’t changed, senior football has: formations developed throughout the 20th century, increasingly defensive, as 3-2-2-3 “WM” turned into 4-2-4, which in turn gave way to the 4-4-2. While the Italians were defending and playing keep-ball before hoping for a lucky break, at Barcelona rebel Johan Cruyff was revolutionising football with positive 3-4-3 tiki-taka, encouraging all players to think defensively when not in possession of the ball, but also be attacking-minded when their team does have the ball.

Since then, football has changed direction again: Cruyff’s understudy Pep Guardiola has implemented his own philosophy right through the Manchester City franchise, to Melbourne City and New York City FC, where – guess what? – Patrick Vieira is utilising his own twist on the 3-4-3 with that “WM” formation everyone thought had died in the 1920s.

Now such innovators have influenced the sport so much that collective pro-active zonal marking is becoming increasingly favoured over individualistic re-active man-marking, and fearless, high-risk, attacking play with lots of pressure far more  commonplace. As I write, the current English Premiership is dominated by teams who either were influenced by tiki-taka, utilise a 3-4-3, adopt zonal marking even on set-pieces, or focus on pressing – or a mixture of all these. That demonstrates how the upper echelons of football have evolved at the forefront of football innovation. Much like Scandinavian social democracy, when something works, why do we still reject it? Because we’re English?! Foolish, more like.

commonplace. As I write, the current English Premiership is dominated by teams who either were influenced by tiki-taka, utilise a 3-4-3, adopt zonal marking even on set-pieces, or focus on pressing – or a mixture of all these. That demonstrates how the upper echelons of football have evolved at the forefront of football innovation. Much like Scandinavian social democracy, when something works, why do we still reject it? Because we’re English?! Foolish, more like.

Grassroots football is always a good ten years behind, but here these themes will be adopted, too, because otherwise players progress, only to have to essentially re-learn the principles of football.

Yes, it’s easier for grassroots coaches to put less preparation time in and just tell everyone to adopt the same old vanilla formation, mark individual players, and hoof it up the pitch. Yes, it’s tough to teach and influence players away from tradition; it’s daunting for them too because again, people fear change.

But when change is embraced – when players are passionate, and keen to learn, and want to challenge themselves and take their game to a whole other level – success follows, both individually and collectively.

But this requires patience, something us Westerners don’t exactly have a lot of. Martial arts in its Far East origins usually saw students spend years at white belt before finally earning a black belt – when the West imported these fighting arts, people were far too impatient, so more colours were introduced as progression points; students were dropping out because they weren’t witnessing more “quick-fix” results.

My heart is with grassroots football; with women’s football. I have no ambitions for myself to go onwards and upwards in any way other than with AFC Unity; without AFC Unity, I wouldn’t be doing this. But there is no reason grassroots football should not be proud, evolve, and be ambitious for itself to improve the quality of football delivery at every level, so that players have different expectations of how much they can learn when they get involved. This is why grassroots football has to be professionalised – not for its players, but in the way it’s delivered, and regulated, rather than letting volunteers run amok venting their weekday frustrations by conducting their training sessions like an army camp, “drills” and all.

It’s why our Solidarity Soccer initiative wins awards; its retention rates are high because the ethos of AFC Unity isn’t just about working together, or skill-sharing, but also about learning without fear – and playing without fear.

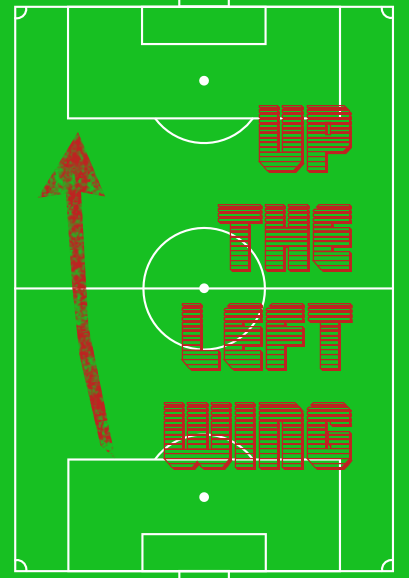

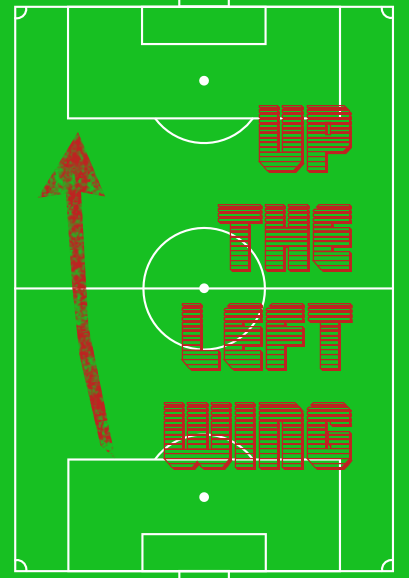

AFC Unity is developing its own football philosophy, one that reflects its ethos – it’s fast becoming a part of our identity because the way you play soccer should reflect the way you are, and terms like “positivity” and “collectivism” don’t really fit with the old ways of football; they apply to the ways we’re trying to nurture.

It won’t be easy – we’ve just thinned out all our pre-existing personnel into two teams before being struck with an injury crisis – but that set-up in the longer term will provide the perfect base for women to progress from Solidarity Soccer, to AFC Unity Jets, to finally representing AFC Unity in its first team, with the football philosophy and style of play running through all of them, so players truly feel the difference playing for us, with what we do on as well as off the pitch, and understand what it means to be a Unity player.

Hope Over Fear.

This can have a massive impact on people’s lives, particularly at this time of year, and is another way of showing that the AFC Unity ethos of collectivism and community is more important than ever.

This can have a massive impact on people’s lives, particularly at this time of year, and is another way of showing that the AFC Unity ethos of collectivism and community is more important than ever.

Following on from our extraordinary success this year in winning the FA’s national Respect Award, and taking Bronze in Sport England’s Satellite Club of the Year awards, we are proud to announce that AFC Unity have been shortlisted in the category of Most Innovative Organisation for the Sheffield Make a Difference awards from Voluntary Action Sheffield who are arguably Sheffield’s leading non-profit support and advice organisation and are based at The Circle, AFC Unity’s registered office.

Following on from our extraordinary success this year in winning the FA’s national Respect Award, and taking Bronze in Sport England’s Satellite Club of the Year awards, we are proud to announce that AFC Unity have been shortlisted in the category of Most Innovative Organisation for the Sheffield Make a Difference awards from Voluntary Action Sheffield who are arguably Sheffield’s leading non-profit support and advice organisation and are based at The Circle, AFC Unity’s registered office.

We’ve always emphasised that AFC Unity measure results differently – that, as a registered social enterprise, we have different targets to meet, different aims to reach for, and different outputs and outcomes than other sports clubs that may be unincorporated associations and just about results on the field.

We’ve always emphasised that AFC Unity measure results differently – that, as a registered social enterprise, we have different targets to meet, different aims to reach for, and different outputs and outcomes than other sports clubs that may be unincorporated associations and just about results on the field. But what does this mean in practice for players?

But what does this mean in practice for players? commonplace. As I write, the current English Premiership is dominated by teams who either

commonplace. As I write, the current English Premiership is dominated by teams who either