By Jay Baker

This will be my last Up the Left Wing column for the AFC Unity website, and I’ll come to the reasons why later on. But obviously this is, and has always been, an opinion piece (disclaimer at the bottom).

At our Awards Night on May 1st, I stressed the importance of keeping perspective on such occasions, because there are two ways of looking at “external validation” of your efforts:

Firstly, if you don’t win a major award, but believe in yourself as a player, then you’ll do just fine. Secondly, if you do win a major award, but don’t believe in yourself as a player, then you’ve still got a lot of work to do. Awards are nice, but they shouldn’t ever be the reason people do anything in life. They should do things because they believe in those things, not because of some kind of external validation. This pretty much sums up my entire approach to AFC Unity!

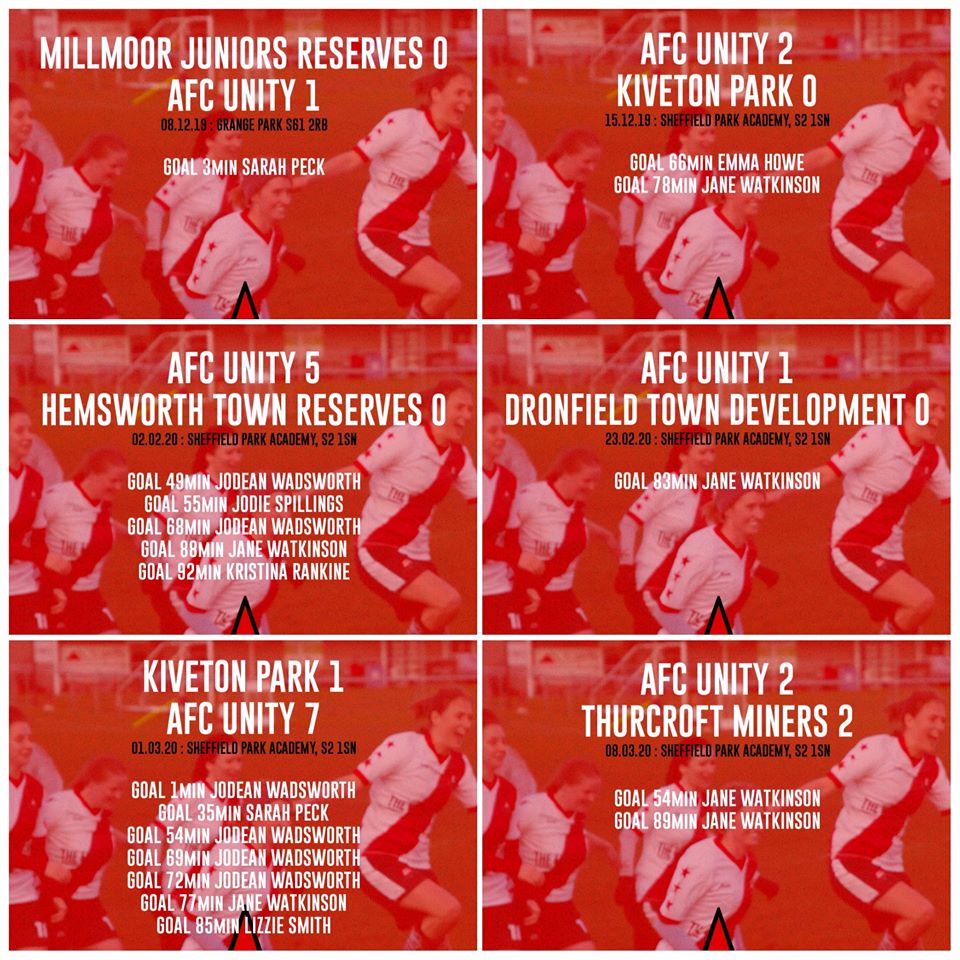

As we finished this past season on a six game unbeaten run in the league, the false importance of “external validation” will be applied to AFC Unity by critics. They’ll say that, since a global pandemic came along and authorities decided to expunge the results, wipe the statistics, and write off the season and all that went into it, then what we did supposedly didn’t matter. To rely on a website recording facts and stats ordained by some authority as valid is probably a good example of the absurdity of external validation in our culture. Our season happened. Our results were real. It doesn’t matter if an authority acts like they weren’t. And I’m very proud of what we achieved.

But it wasn’t some sort of lucky break.

People forget that back in our first season, 2014/15, we cobbled together a team of players and finished third, gaining promotion from Division Three into Division Two. The next season saw us celebrate a year-long unbeaten run at home, but these were tough times. Starting a football team without making clear what your aims are and without being bold about what your ethos is, inevitably means you attract players who just want to play football for your team in the same way they’d happily play football for any other team: they show up, get some game time, and go home, and as long as their own individual needs are met, they’re fine. That’s not why we set up AFC Unity – to be like any other team.

As I took on a little self-belief and moved from a mere “managerial” (yuck) role into that of a Head Coach, I was able to draw on my experiences as a community and youth worker and from social enterprises and emphasise the importance of doing things differently – adopting an approach that meant the individuals were valued for what they formed as a team; that individual traits can be harnessed into a creative, triangle-based system and a style of play that eschewed the traditional grassroots 4-4-2 and direct “long ball” approach. I wanted every single player on the pitch to play an equally important part in the passing-orientated football that reflected the collectivist ethos of the club itself – the goalkeeper as the first attacker, and the striker the first defender; everyone front to back absolutely valued. That didn’t sit well with traditional players who liked individualism; some had bullied teammates – even their own mates who’d complain to me in confidence – and I went to great pains to resist that culture of individuality and bullying, confronting it away from the football training but protecting the rest of the team as much as I could. Even I myself was essentially bullied, and even harassed and stalked, I started having panic attacks (and still do sometimes) and my health and working life were negatively impacted, but I decided to keep going.

And in fairness our ethos and commitment to developing safe spaces also attracted more players, and in our third season we tried to meet the demand by setting up a second team and entering them into the third division. After the bullies had finally left behind a void in the roster, the remaining first team players had a string of life changes and injuries that decimated the squad the club was supposed to be driven by and yet suddenly found itself trailing near the bottom of the second division, and I was forced to expedite call-ups from our already-struggling second team, which finished it off. What followed, in the fourth season, was a single amalgamation of players from the entire club into one team, which obviously took time to mesh.

And then by the fifth season we were really onto something – we had a team of players who all bought into what we were trying to do, were all focused on mastering a fairly sophisticated style of play and a system to fit it, and focused entirely on the process rather than the results, because they accepted that if you master the process, the results eventually simply take care of themselves. The easiest thing in the world is to play direct, rely on a few key players, and get wins – and I’ve seen so many teams do this, many of whom enjoyed immense success then collapsed shortly after. I used to tell my team, “we’re playing the long game, not the long ball game.” I began telling beginners and non-beginners alike at our Solidarity Soccer development programme, that Johan Cruyff always made the wonderful point that if you want to do track and field, it helps being strong and fast, if you want to play basketball it’ll help you if you’re tall, but with association football, you can be any size or shape: that’s why the most important, most crucial thing they learn is how to pass a ball with accuracy, at the right pace. That’s the most important thing. If you can’t do that, you can’t play beautiful football, as it should be played. Passing is the foundation that every other part of football is then built on.

And so in that fifth season we made history and retained every single player who was able to continue playing for us; nobody left to go to another team, even though our commitment to “process over results” left us at the bottom of the table, working away on our passing football. I’d tell the team that when one day we started getting those results, when the losses became draws and the draws became wins, we can then know in our hearts it wasn’t a win like any other, but a win through playing football the right way. There’s pride to be felt in that.

And in the sixth season, of course, we did it. We played – I truly believe – the best pure football in our division. And we went on a six game unbeaten run in that division. And we’d have done more. It took a global pandemic to stop it.

So no, it wasn’t some sort of lucky break; it was a painstaking building process to that point. My coaching may have developed tactically (I learned more and more every season, and became much better at reacting quickly with my decision-making during the game, in no small part because of Jenna Bacon running first aid, leaving me to just focus on the football), but I’ve never really changed my approach; it was always about the team, about what training needs to be done rather than showing off what I’d learnt or delivering speeches for the sake of it. There’s already too much “mansplaining” in football.

Rather than it being a lucky break, it’s about finally having players who bought into the approach, staying with the team when you’ve finished bottom of the league, solidifying that level of loyalty, and then playing the best football, and going on a six game unbeaten league run. And that’s not to say I wasn’t still sometimes struggling to get my approach across in a culture where matchdays feel like a war zone and I’m the odd one out in amongst the toxic masculinity. People accept what they think they deserve. You have to help them realise they deserve better, and should expect better (yes, even from me). Of course, criticism fades when you’re on a good run, and that’s not a coincidence, as many coaches at all levels will tell you. I knew, rationally, logically, I’d face defeats again, and rough streaks again, and once more I’d have to face the looming spectre of the traditional football culture narratives regarding shouting at players, and playing long balls, and the like. Yawn.

Like I said, it took a pandemic to stop us, but we know what we achieved. I’ll always have those memories, and proof that football can be done in a different way, and a better way, and still get results. A couple of weeks before the pandemic stopped the season, I’d been going to the gym, travelling on trains, trams, and buses, and shaking hands at community activities and, in fact, pretty much unwittingly doing everything to expose myself to a virus I hadn’t been taking into consideration, or taking anywhere near seriously enough. With symptoms, Jane and I went into isolation, as did other players, and then we became quite ill – the cramps I had left me in bed a few days, I’ve been unwell ever since, and Jane’s breathing became worse enough to warrant check-ups, tests, x-rays and CT scans, to the point where she couldn’t (and can’t) walk around the block without struggling to breathe properly (and now has an inhaler). We became the first team in our league, as far as I knew, to pull out of a game because of the pandemic and related health concerns. Then about a week later, after a bunch of games that needlessly took place, everyone followed suit “because t’government said.” Yes, that honest, kind, intelligent, responsible, caring, considerate, and competent government, eh? Which one is that, then?

As a club, we continued. We had our Awards Night, and there continued to be caring dialogue in our chat group, and wonderful examples of mutual aid, in addition to many players contributing their subs to Sheffield’s food bank network, since we weren’t training or playing. And for good reason. Without a vaccine at that time, the causes of infections and deaths were largely due to non-essential work and activities. And while figures from the past, from John Stuart Mill, to Benjamin Franklin, to John Maynard Keynes seemed convinced that by 2020 technology would have advanced to the point where we’re working, as humans, maybe two or three days a week each on crucial things only, capitalism has in reality created, by 2020, what anthropologist David Graeber calls “bull*** jobs” and then after a few months of infection and death rates dropping, in the absence of a vaccine our government wanted us to return to “business as usual” by bribing us with vouchers to keep the economy going that keeps the rich getting richer in the absence of a general strike. With its institutions and sponsorships, football is a part of that; they were happy to scrap last season, likely knowing full well they’d start another season in 2020/21 and offensively compare another “lockdown” to using nuclear weapons – quite the opposite, since everything going back to how it was in March is the true harm to millions of people; there’s a reason it got so bad by April.

For all its actual destruction, and the long-term effects on us we don’t even yet quite understand, this pandemic (the first of many, if we don’t change the way we do things), has shown a lot of good in people. With businesses putting people in harm’s way, there have been labour strikes. With people unable to sustain income, we’ve seen rent strikes. And the Black Lives Matter movement has been an inspiration. People have begun to reevaluate what matters in our society. What jobs must we be doing? What gives things value? What’s worth putting ourselves at risk for? And are we going to recognise every person’s varying vulnerabilities as humans?

It was this mentality that left me refusing to return to football during a pandemic. Our last season was scrubbed and cancelled because, for a brief moment back in March (though better late than never), we accepted that life is too valuable to risk for affiliated league football. To return to league football now, and recreate the circumstances that spread the disease so much in the first place, would be to accept that our last season was cancelled for no reason. To refrain from playing in March means to refrain from playing now. There is nothing stopping people from finding space in the park and kicking a ball about in a physically distanced manner, or full-on with people they share a home with. But to dive back into affiliated league football now – especially with the news of a vaccine bringing hope for the near future anyway – would be not only chaotic and stressful, but irresponsible, disjointed, and divisive. Unity is about “all for one, one for all.” This is why I will not return to coaching in these circumstances (even if I was able to somehow travel to trainings and games, home and away – perish the thought). Our behaviour patterns can avoid spreading infection and destroying lives on a larger scale.

This said, I do not subscribe to the negative narratives and name-calling of “Covidiots” (unless perhaps I’m talking about the people in positions of authority). When many of us are being told to go into workplaces and other unsafe environments, inevitably people will want their leisure time too, whether that be heading to the beach, or to the park…but again, it doesn’t have to be affiliated league football as part of the old system, the old way of doing things. My choice is to refrain from being a part of that personally, and it’s then for others in society to reconcile. Our collective memories recall the “lost season” and our six game unbeaten run in the league, and I want history to also show that I did not take part in a return to affiliated league football during a deadly pandemic.

I’ve enjoyed contributing to the Up the Left Wing column because as mentioned I’m uncomfortable giving speeches for the sake of it, or when people don’t want to hear them! This is an opportunity for people to know my views if they’re at all interested. As we’ve progressed with AFC Unity to the point where players have a say on how their money is spent and how the club is run, we’ve tried hard to put the team at the forefront of the club, and with that this column should be given to them. My views can be found away from AFC Unity, at my own website, where I’ll try and archive these column entries.

What AFC Unity does next is something I do not know at the time of writing, and therefore I don’t know what my future is in terms of my own involvement. I don’t know if the culture of football itself has been ready for something like what we’ve done, but I take great pride in our ethos and our football philosophy, and the way we’ve cared about and valued individuals, and developed safe spaces. And it’d be nice to see it continue, with patience, loyalty, togetherness, solidarity, and unity.

I want to thank everyone who has stuck with AFC Unity through the years, believes our collective way is the right way, and a special thanks to those who have contributed so much time and effort behind the scenes, and continue to do so to this day.

The views expressed in “Up the Left Wing” are those of Jay Baker and do not necessarily reflect those of AFC Unity or any of its personnel or players

It’s pleasing to look back on

It’s pleasing to look back on

But for a brief moment – particularly at the beginning of our affiliated football journey – AFC Unity have never been at the bottom of the league. We’re there now.

But for a brief moment – particularly at the beginning of our affiliated football journey – AFC Unity have never been at the bottom of the league. We’re there now.